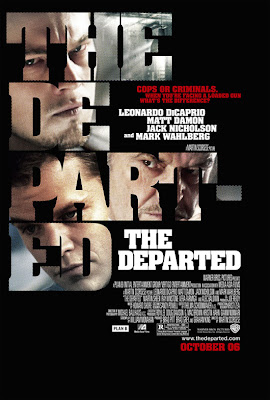

Today’s morning news announced Martin Scorsese as the winner of the Golden Globe award for best director. Of course, in case you are not familiar with his name, he’s the director of the movie “The Departed.” Now, I am one of those people who feel that Mr. Scorsese deserves more than an invitation to the Academy Award ceremony every year, declaring winners and paying tributes to past Hollywood filmmakers. It may border on criminal that he did not, so far, get to hold one of the Oscars up on the stage for his past masterpieces: Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, The Goodfellas, The last Temptation of Christ, Kundun etc… well, you get the idea.

Of recent, however, one of the least accomplished is “The Departed,” in my opinion. Although the film’s basic plot is borrowed from the Hong Kong film “Infernal Affair,” I expected much more character rumination worthy of his craft. Of course, even Scorsese he himself will acknowledge that he hasn’t made an enduring masterpiece with “The Departed” as he had confessed in one of the interviews he gave prior to the release of the movie. He had said , including “The Aviator,” something to the effect that these weren’t the kind of films that he would incubate for a long time as his last pet-project “Kundun.”

Whatever prompted him to commit his energy to this film is really not my point here, nor this review. It, nonetheless, denotes the degree of passion he brought to bear on the project. Now, one may argue it is unfair to judge a film purely based on the director’s passion, vigor or personal affinity to the project at hand, after all we have seen so many Hollywood films that seem so full of passion and energy but fail to deliver on its promise. However, it would be equally dismissive of Scorsese if we consider him to be a Hollywood creature.

What I saw in Scorsese’s other masterpieces was the personal redemption his characters try to achieve in vain through the means of killing, prostitution, gambling, lying, meditations, love, sex, betrayal etc…basically, all of the traits that can be found in the human history. One of his hallmarks is gaining self-consciousness through one’s suffering whether it be physical or mental. Most notable characters embody this quality are Jack LaMotta in “Raging Bull” and Travis in “The Taxi Driver.” The protagonists, in these cases, are nothing more than people who feel that they have to do something. But for what? We do not know. Even if they do achieve their goals by way of whatever means available to them, the end results for all these characters are same as before they set out on their journey, that is, their surroundings.

Jack LaMotta gets a beating in the boxing ring as a way to receive salvation through his self-mutilation. Just as the Passion for Jesus was the only way to accomplish his divine mission, Jack’s suffering in the ring is the very act of the Passion for him. Much as the theatre stage represented for Shakespeare the world, the ring in “Ranging Bull” serves as the world we live in, and the physical abuse and suffering Jack has to endure, our anxiety and pain we must face in the world.

Travis, on the other hand, sees his self sacrifice, in the likeness of Jesus, as a God’s divine calling that must be answered to save this world from the evil. His redemption comes from good deeds by getting rid of a politician who lies. He sees himself as a savior of sorts. As a result, he throws himself at the hatching of a plan to kill an evil politician who is accountable for all the wrong things in the society.

If all of this has religious overtones, it does because Scorsese deals directly with the issue of life and death in modern society and the means to overcome it – transcendence. Thus, we get films like “Kundun,” “The Last Temptation of Christ.” These two films, he had once said, are the projects that he kept close to his heart for 10 years. The overarching theme in these films are, of course, what it means to give oneself to the need of the concerned society when the outcome is more or less the same. It’s a personal question asking only to himself, not a collective one. He does not have the answer to his question, nor does he expect his audiences to draw one from his. Films by Scorsese are as far from being didactic as oil is from water in substance. It is as much about his own spiritual journey as his characters’ own ambivalent future.

With “The Departed,” we get neither a question nor a working out of one. Only thing we get is confusing multiple narratives that coalesce more or less at the end to an unsatisfying ending. There is no redemption, no ambivalence... Characters in TD are so sure of their actions, we are hardly given an chance to identify with them. Here, the difference between the good and evil is distinguished so much so that one is forced to rely only on gores and violence to justify the admission fee. In the past renderings of his characters, the good and evil is not so sharply defined. It is only the inner self that creates a moral universe where he’s the ruler, making his characters the prisoners of their own world, whereas, with TD, the only thing concerns is narrative twist. As such, development of character takes the back seat.

I will concede that Scorsese does try to render the law enforcement as a complicated beast that more or less rivals the actual bad guys in virtue, and perhaps surpasses in exploitation, in which code of justice is as weighty as a piece of paper. Yes, on the surface this does seem like Scorsese’s familiar territory where, once again, we revisit the grey world of good and evil. But this is only on the surface. How the characters in TD that occupy the film’s temporal space of nearly 2 hours see themselves through the eyes of its creator is still not clear because they are not given the emotional space that’s required for these characters to be introspective.

I do wish Mr. Scorsese to receive some kind of major recognition in the form of prestigious film awards like the Oscars or the Cannes, but I would be even more delighted if it was for the film that’s worthy of his art.